BY BRIAN BROWN

Purchasing a new piece of apparatus for your department can be both a rewarding and an educational experience. The apparatus purchasing committee (APC) is dynamic in nature, which means that it may include driver/operators, officers, paramedics (if the specification will be advanced life support/basic life support capable), chief officers, internal purchasing representatives, and an IT representative and should always include an emergency vehicle technician (EVT).

The committee is a dedicated group with a fivefold purpose: analyze changes in the department, stay current with manufacturing processes, remain up to date on technological innovations, be versed in apparatus and equipment safety, and be fully aware of fiduciary responsibilities.

One unexpected aspect of the APC is the emotional and rumor mill. Confidentiality is important; otherwise, a member of the committee may share a little snippet of the process, and a chief’s vehicle transforms into a heavy rescue and three tillers! Per National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1901, Standard on Automotive Fire Apparatus, the apparatus committee “chairman” is the authority having jurisdiction (AHJ), and it sets the direction and goals for the committee throughout the process—and does its best to manage rumor control.

The majority of APCs work very well together and fulfill their duty admirably. Others do not and hire a consultant. Normally, committee members sit at the table with their list of personal whims, wishes, and desires that can, quite commonly, become controversial in the process. That’s when a diligent APC chair should step in to keep the meeting and members in check. The committee chair now has to monitor personalities and establish committee-level priorities. That in itself may be more challenging than agreeing on a make and model and what color is on the apparatus. As work progresses, internal committee priorities may need modification and restructuring. That’s where the “Need vs. Want” comes into play.

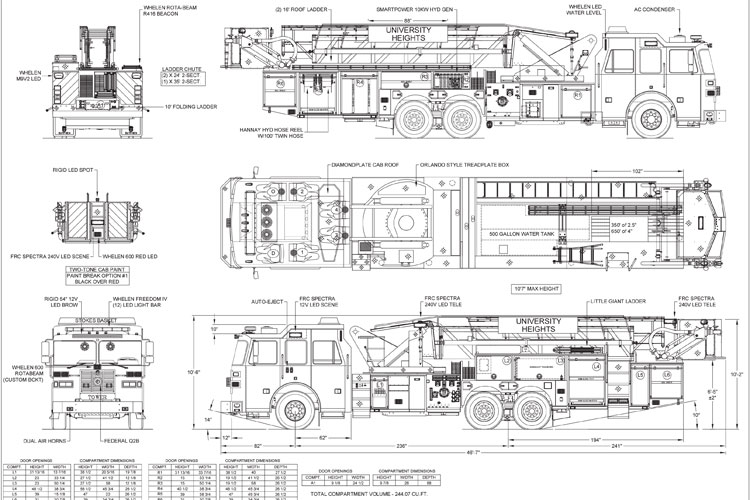

In an effort to provide cost-effective emergency services on a limited budget, fire departments are now looking for ways of incorporating operational efficiency in specifications that mold the designs of new apparatus purchases. In other words, apparatus and equipment are designed for operational functionality and not just good “curb appeal.” For many years, departments used a detailed specification that could be as many as 2,275 pages with an index, specification, and appendices that covered every facet of the apparatus including the type and size of filters, wiring color and gauge, bolts, valves, differential ratio, diamond plate grade, door hinges, hosebed vinyl texture and thickness, and more. Currently, research has been geared to look more toward an operational specification that provides information about the jurisdiction’s geographical location including how many square miles and the population it covers. Using this specification style also provides the criteria about the departmental personnel, Insurance Services Office (ISO) rating, rural vs. suburban vs. inner city, cab size, engine and drivetrain needs, equipment, hose, water tank size, pump size, etc. These critical items provide the specification foundation that needs to be reviewed by a diverse APC with no more than eight, and no fewer than three, individuals.

MEASURING SUCCESS

The APC will critically assess all specifications, inspections, testing, and documentation for all the departmental emergency apparatus. One way to ascertain APC success indicators is to establish a standard that the committee chair can use to measure and monitor the effectiveness of a program necessary for an organization or a project to achieve its mission. Certain success indicators will include the following:

- Cost effectiveness and operational value.

- Ability of department personnel to efficiently operate on a day-to-day basis.

- Ability of standardizing purchases to create lower costs related to the initial purchase as well as ongoing maintenance and repair.

- An efficient purchasing, replacement, and maintenance program for all apparatus.

- Decisions bound by budgetary constraints in addition to aligning with the long-term goals of strategic and capital replacement programs.

- Determination that the design and function of the emergency fleet provides adequate safety features, which includes ergonomics for the end users.

ECONOMIC IMPLICATIONS

Another issue is the importance of economic variables in a replacement analysis. Economic data are frequently overlooked from replacement analysis, possibly because it is extremely difficult for fire departments to extrapolate internally, or they cannot be obtained from the fleet maintenance division. But these data are imperative to use in projecting inflation; depreciation; discount rates; and the importance of such variable costs as repair and maintenance, downtime, and the number of calls in the district to which the unit will be assigned.

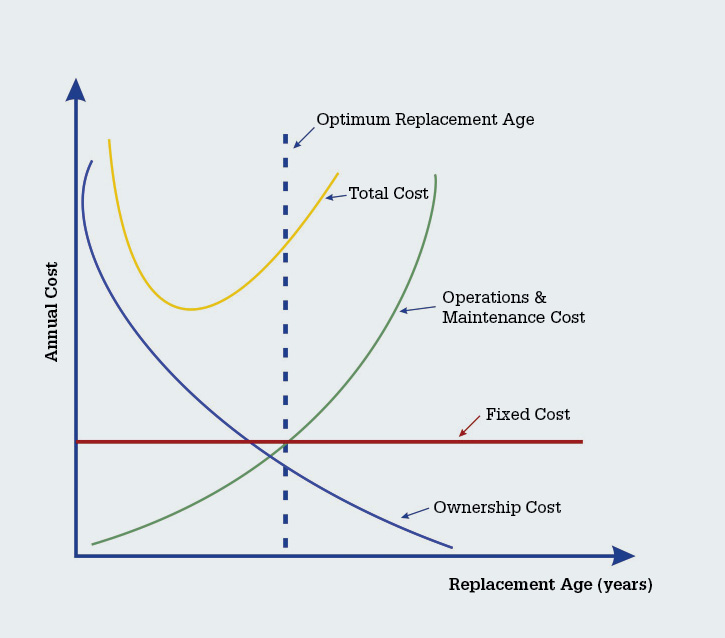

It is assumed that economic indicators are critical components of replacement analysis because they serve to adjust apparatus cost through time. These indicators have a considerable impact on both apparatus capital and operating budgets. The economic life of a unit refers to the length of time over which the average total apparatus cost is the lowest (see Figure 1). Total apparatus costs associated with ownership of equipment include the following:

- Depreciation.

- Operation and maintenance.

- Downtime vs. availability.

- Obsolescence.

- Operator training time and costs.

- Parts inventory via factory or dealer.

- Value of money (i.e., lease interest, bond interest, alternative capitol).

- Value and inflation.

- Cost for reserve apparatus for maintenance or major repairs.

- Cost effectiveness.

- Operational value.

- Technological value.

Figure 1: Economic Theory of Vehicle Replacement. (Figure courtesy of author and John Stouffer.)

While preparing the apparatus specification, remember the median fire truck life is 15 years. Many times, obsolescence occurs before 15 years when parts for the apparatus cab and chassis, body, aerial, fire pump, tank, foam system, and other associated equipment are no longer available or have been replaced by improved design and technology. Obsolescence is an additional operating cost that has a significant impact on downtime, resale value, and depreciation. During the life of the apparatus, these costs will vary. Some areas will increase, while others will remain consistent, and other areas will actually decline. The value comprises the total life cycle cost of the apparatus that is relevant to its economic life.

REPLACEMENT

A vehicle basically has three lives: service life, technological life, and economic life. Service life is the amount of time the vehicle is capable of rendering service. Technological life represents the relative productivity decline of the vehicle when compared with newer apparatus. The economic life is the total cost associated with the apparatus over a period of time. A department must pay particular attention to the economic life of the apparatus. Departments that do this actively track the age, condition, maintenance schedule, engine hours, and miles or fuel consumed as the vehicle age costs increase. There may come a time when the apparatus must be replaced to reduce the total cost of operation.

The department should determine when the vehicle needs to be replaced based on cost and when funds are available. If a piece of apparatus is due for replacement, project the total costs of the current piece of apparatus for the following year, and then compare that cost to the cost of a new piece of apparatus. The difference between the two figures is the argument for not keeping the vehicle past its economic point of replacement.

COMMITTEE SCENARIO

Here is a scenario using an imaginary committee comprising a captain, engineer, fleet EVT, and APC chair who are considering the purchase of a midmount aerial platform. The initial emergency warning lighting specifications were to specify a “well lighted and safe custom apparatus with enough emergency lighting to protect the crews while blocking on the highway.” The engineer, the department’s senior engineer, wants to redesign the lighting package during the mid-inspection at the factory. He says he’s the one in charge when the rig responds, and it should be set up to his liking.

The captain, the most seasoned officer of the group, disagrees and wants more scene and ground lighting. He says the emergency lighting is sufficient per NFPA 1901 (2006 ed.), Section 13.8: Optical Warning Devices. However, the scene and ground lighting was overlooked. He wants to ensure the area where the crew gets out of the truck, the area around the compartments, along with the area in which they are working will be well lit to avoid any tripping, stumbling, or falls. The captain also expounds on the amount of workers’ compensation claim injuries the department has had over the past 18 months because of insufficient ground and scene lighting.

The engineer claims he is the one who actually drives the truck and provides the most safety to the community and the crews always arriving safe on scene, so his emergency lighting choice should have preference. He also notes the minimum optical power requirements per zone, safety and accident studies, and possibilities. Reading between the lines, he wants every lighting feature known to mankind and those not yet invented.

That’s when the committee chair must intervene, noting the original specification they helped put together and the amount of time spent on just the lighting package. Committee members don’t always agree, and pet peeves and stubbornness can stall the process when the need-vs.-want card is thrown in the mix.

CAPITAL PURCHASE SPECIFICATION PROCESS

Another consideration is standardizing apparatus. There are a number of advantages to standardizing apparatus not only operationally but also during the specification process.

The capital purchase specification process will bring improvements to the department’s operations for all areas, decreasing annual operational costs while improving in-service availability. Other advantages include the standardization of apparatus, which improves the proficiency of driver/operators, efficiency of the apparatus, and current technological advances and optimizes vehicle use. Apparatus standardization will improve overall agency efficiency, the specification process, and emergency response effectiveness because of consistency and training familiarization while minimizing factory change orders.

When the resolution has been made, and the APC for your department is finally bringing it all together, make sure to review the vendor qualifications to ensure a solid working relationship with the dealer and factory engineers, parts availability, warranty, and that the vendor provides “Best in Class” customer service. With all the new technology, be sure to relate to the vendor that this will be the truck your department will be using and maintaining for many years to come and needs to be operationally functional, reliable, and safe.

BRIAN BROWN is the bureau chief (ret.), fleet services for South Metro (CO) Fire Rescue and owner of Fire Service Solutions, LLC and Complete Fleet Consulting, LLC.